Illicit Drug Surveillance for Harm Reduction

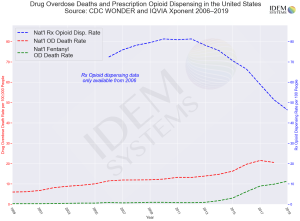

U.S. drug overdose deaths have increased almost every year since 1999, with 2018 being the only year of a slight decline. The federal government’s drug policies targeted prescription opioids to address this issue. The thought was that the overprescription of prescription opioids was leading to diversion of those prescriptions from the prescribed patient into the hands of non-patients. For example, a person stealing pain pills from their grandma’s medicine cabinet and subsequently selling them to his/her friends is drug diversion. The national trend of declining prescription opioid dispensing started in the early 2010’s, as a result of federal drug policies’ efforts to minimize opioid diversion and curb opioid overdoses.

Data (above) show that these drug policies that restricted doctors from prescribing opioids to their patients did not have much of an impact on curbing overdose deaths, if any, on a national scale. In fact, researchers and experts suggest that the reduction of opioid prescribing may have contributed to the increase of the national overdose death rate in the mid-2010’s. By tapering patients’ supply of safe prescription opioids necessary to manage their debilitating pain, these policies have been said to actually drive chronic pain patients to compensate for their reduced prescriptions and seek unsafe forms of pain management such as illicit heroin.

As America made its way into the mid-2010’s, there were multiple at-risk groups of people within the population: people with addiction, teenagers and young adults who use drugs recreationally, and the growing number of chronic pain patients seeking alternatives to manage their pain because their doctors were no longer able to legally prescribe them with an adequate amount of prescription opioids, just to name a few. The use of illicit fentanyl and fentanyl analogs increased in popularity as a common additive in the illicit drug supply, mainly in heroin (the addition of fentanyl made the heroin more potent). Even with prescription opioid dispensing rates decreasing across the nation, the national drug overdose death rate continued to increase with a notable surge that correlated with the surge in the fentanyl overdose death rate around 2015 (see the red dotted line and green dotted line in the graph above). According to the data, addressing the drug epidemic by cutting off patients from prescription opioids had no overall positive effect on drug overdose deaths in the U.S. Non-opioid drugs such as meth and cocaine, as well as other illicit drugs were contributing to overdose deaths in the 1990’s, 2000’s, 2010’s, and still do so in the 2020’s. In today’s drug epidemic, illicit heroin has become a bigger danger in the black market as the addition of illicit fentanyl grew more economical and practical for suppliers; Counterfeit pills and tablets have become more prevalent; Counterfeit Xanax and counterfeit prescription opioids are found to contain unknown amounts of illicit fentanyl and/or fentanyl analogs instead of the correct active ingredients found in their authentic pharmacy-grade counterparts – and multiple national stories have been published about teenagers and young adults consuming these counterfeit drugs, not knowing they contain fentanyl and thus, accidentally overdosing. Counterfeit Adderall that is actually methamphetamine in tablet form has been encountered by law enforcement in many regions in recent years. Many people within these at-risk groups are unknowingly consuming fentanyl or meth and are being poisoned. How do we, as a nation, address these illicit drugs and begin to curb the drug epidemic?

Drug policy experts often point to ideas such as more effective drug education, broader access to treatment for opioid misuse disorder and/or mental health counseling, better drug interdiction capabilities for law enforcement, and promoting harm reduction methods. In prior articles, I have discussed IDEM Systems’ intention to develop more advanced field drug test kits consisting of hardware and software tools for enhanced law enforcement drug interdiction. In this article, I propose extending the use of the same innovative hardware and software tools for illicit drug surveillance as a form of harm reduction.

When I read about harm reduction in the context of drug use, I typically come across the ideas of clean syringe exchanges to prevent the transmission of bloodborne diseases (e.g., HIV, hepatitis, etc.), fentanyl test strips so that users can test their drugs before consuming them, carrying Narcan/naloxone and being ready to use it in case of an opioid overdose, and safe consumption spaces with professional healthcare personnel to administer a safe supply of heroin or other opioids. I recently read a journal article written by Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a University of California San Francisco drug policy expert, and he mentioned the concept “Surveillance of the Drug Supply”, which essentially consists of monitoring, identifying, and collecting data on the regional drug supply and encouraging the sharing of such data between the public safety agencies (i.e., law enforcement agencies) and public health agencies.

IDEM Systems’ technology intends to collect data that would allow for this kind of drug surveillance. The initial idea was for law enforcement agencies to have access to the data to aid in their drug interdiction activities. Now considering the concept of surveilling the illicit drug supply, the same data would be highly beneficial if shared with public health agencies.

Imagine the following hypothetical use case of our technology: over the last week, police in the area have encountered 6 drug cases involving counterfeit Xanax pills and counterfeit Adderall pills. The IDEM Systems drug test was used to determine that the Xanax pills contain various fentanyl analogs and the Adderall pills contain methamphetamine and caffeine. The police would share this real-time data and make it immediately accessible to the county public health department. The public health department could monitor the data and, as needed, make public service announcements and publish press releases to alert the community and/or push notifications to organizations that work closely with at-risk populations about these counterfeit drugs in the illicit drug supply. Additionally, finals week may be coming up for the local universities and Adderall and Xanax may be in demand on campus for focusing, studying, reducing anxiety, etc. The public health department can push alerts directly to the universities’ public safety departments, which can push text and email alerts to all of their students to quickly warn them about the counterfeit pills they may encounter in the black market. By spreading awareness about these tainted drugs in the region, potential users would be more careful when consuming illicit drugs or just avoid them altogether – which would minimize overdoses.

The ability to collect drug data in real time as portrayed in this scenario would change the paradigm of how government agencies handle the many aspects of the drug epidemic. Our public officials can no longer pretend that the drug epidemic will just work itself out. They must be proactive in combating it and finding innovative solutions to such a significant societal problem. That includes supporting initiatives that promote effective drug education and harm reduction, passing legislation to fund the development of technologies that will improve public safety and public health, and encouraging public-private partnerships to catalyze the generation of new ideas to help the people they represent. Last year, a record 93,000 people died of a drug overdose in America. Public officials on the federal, state, and county/municipal levels must do more to influence drug policies that adopt expert recommendations to combat the drug epidemic.

You can follow Dr. David Nash on Twitter @DrDavid_IDEM